La Main Flottante, 55, Passage des Panoramas, Paris, 2002, [48], carries a deft nod to Surrealism in the form of a disembodied hand mysteriously hovering over antique envelopes in the Passage des Panoramas. The image is intriguing, carrying with it the knowledge that the hand likely belongs to the proprietor reaching to show one to a client; but it also creates a willingness in the viewer to believe that it hovers there permanently, as part of the magic evoked by the extraordinary Passage des Panoramas and its storied history. The Passage, a beautiful glass-roofed arcade built in 1799, now houses an eclectic range of antiquarian bookstores, antique dealers, engravers, restaurants and shops. Its relationship to photographic history is important in that it is associated with Louis-Jacques-Mandé-Daguerre’s dioramas and their spectacular and magical light effects that enthralled Parisians in the 1820s and ‘30s as an historical precursor to the cinema. Daguerre famously went on to invent photography in the form of the Daguerreotype - the invention being announced to the world in 1939. The Passage des Panoramas thus carries the aura of this vital piece in the development of the medium with which Ron Hurwitz now works, and for him, and for others aware of its significance, provides a background note to this captivating and slightly unsettling image.

Ronald Hurwitz’s Paris-based works have been collected by the Maison Européenne de la photographie, the Musée Carnavalet and the Bibliothéque Historique de la Ville de Paris, all three of which play a central role in the School of Image Arts’ Masters program in Photographic Preservation and Collections Management. The RIC is pleased to now include the above three prints in the collection.

by Peter Higdon, Collections Curator, Ryerson Image Centre

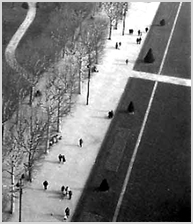

Allée Anatole France, Paris, 1986

Print No.s 46 - 48

Ronald Hurwitz’s photographic practice began in 1979, during his career as a violist in the Toronto Symphony. Within two years he had exhibited works that were exhibited at Toronto’s Déja Vue Gallery, and won awards there in a juried competition. His discovery of the medium launched a concentrated exploration of its history and expressive capacities, and has resulted in a diverse body of work that includes urban spaces in New York, Paris, and Venice, portraiture and still life studies. The works in this donation have Paris as their focus, and are subtle and sensitive observations of details of that great and engaging city. They quietly reference the enduring pleasures encountered in a setting that has long drawn photographers, and simultaneously reference and honour photographic history and its definitive moments.

Allée Anatole France, Paris, 1986 [46], is both an observation of a Paris street from a high viewpoint and a graphically satisfying abstraction of that environment. The visual balance is achieved through the relation of the broad diagonal stroke of the Allée as it traverses and dominates the space, to the whimsy of the non-symmetrical arms that branch off to its left and right. The regularity of French park design is acknowledged in the rendering of the two rows of trees that bisect the broad graveled pathway, and the espaliered shrubs that dot the ground at regular intervals on the un-trodden grass to its right. As contrast, strollers dot the public gardens, bringing the randomness of human activity to bear on the highly constructed space. The photo-historical reference here is to André Kertész’s experimentation in 1927 with photographing Paris from above, in particular from the first platform of the Eiffel tower, resulting in a previously unseen view of the ground that ruptured expectation in the viewer and forced a fresh seeing of a commonplace urban surface. This artistic strategy was newly in the air in the 1920s, being significantly practiced slightly earlier by the Constructivist Aleksandr Rodchenko, whose camera angles dramatically led the viewer’s eye both upward and downward, and resulted in visual patterns previously unrecognized.

Ronald Hurwitz Photography 32-5 Tyre Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M9A 1C5 416 465-5890